- Speculation about a fresh liquidity injection – the ECB’s flood of liquidity has been a decisive factor ensuring favourable financing conditions;

- Periphery banks are particularly dependent on inexpensive central-bank liquidity – but time is pressing on account of regulatory requirements;

- ECB is in a dilemma (conflict between supervisory/monetary-policy roles) – new TLTROs are likely to be justified by weak lending in Southern Europe.

Over the past few weeks, speculation has been rife that the ECB may well be poised to launch a fresh liquidity injection for European banks. In principle, new long-term tenders would enable the monetary custodians to ensure that financing conditions remain favourable even after the current TLTRO-II operations have matured. What is noteworthy is that this particular topic is already being keenly debated; after all, the first TLTRO-II tender will only be falling due in June 2020.

This sense of temporal urgency is a result of regulatory requirements for banking institutions. If the residual maturity of cash flows falls below a one-year horizon, they no longer count when certain parameters (net stable funding ratio / liquidity coverage ratio) are computed. Against this backdrop, banks from the European periphery, in particular, could be compelled to shrink their balance sheets in order to comply with the respective statutory ratios. A possible undesirable knock-on effect of this would be more limited, and more expensive, bank lending. In addition, it could be conceivable that banks would prune their government-bond holdings, which might possibly entail higher risk premiums. In recent years, Italian banking institutions, in particular, have purchased a substantial volume of domestic sovereign securities in order to set up carry trades. We consider a fresh injection of liquidity from the ECB, as a measure aimed at counteracting a widening of risk premiums, to be distinctly probable. However, the monetary authorities would probably wish, at the same time, to avoid making the impression of only rushing to the aid of banks and government-bond markets in the periphery of the eurozone when launching fresh long-term tenders. The ECB’s top echelons would therefore be likely to mainly accentuate that bank lending was slowing in Southern Europe when communicating such a step. On the other hand, that drives home the conflict of interest in which the ECB finds itself on account of its dual role as banking supervisor and monetary custodian.

We think that there is a distinct likelihood of the euro area’s monetary authorities deciding on fresh liquidity operations at the next Governing Council meeting, scheduled for 7th March. The expected downward revision in the ECB staff’s economic-growth and inflation projections ought to make it easier for Team Draghi to justify the need for further liquidity measures. However, the interest-rate bonus linked to net lending could turn out to be somewhat less generous than in the terms of the current TLTRO-II operations in order to signal the ECB’s ongoing determination to return to monetary-policy normality but also to resolve the bank’s conflict between its two roles. But one rather interesting question remains: whether fresh targeted longer-term refinancing operations would merely delay the ECB’s endeavours to normalise its monetary policy – or whether such endeavours have, in fact, already ended in complete failure.

The ECB is cought on the horns of a dilemma

The ECB is threatening to lose itself between its monetary and regulatory roles

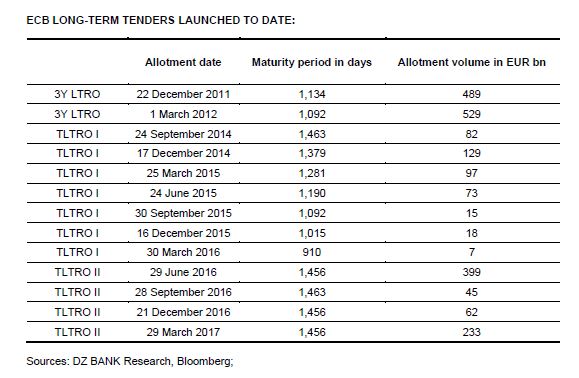

Longer-term refinacing operations are a tried-and-tested monetary-policy instrument which has already been deployed frequently in the past. Most recently, commercial banks were offered such longer-term central-bank liquidity in summer 2016. Starting in June of that year, the central bank launched a total of four quarterly Targeted Longer-Term Refinancing Operations (TLTROs). The objective of these long-term tenders was to stimulate bank lending across the eurozone. A particular stimulus for the zone’s banking institutions was that counterparties whose eligible net lending exceeded a certain benchmark benefited from an interest-rate bonus. Euro area banking institutions seized this opportunity with open arms, taking up more than EUR 700 billion of central-bank liquidity via this route.

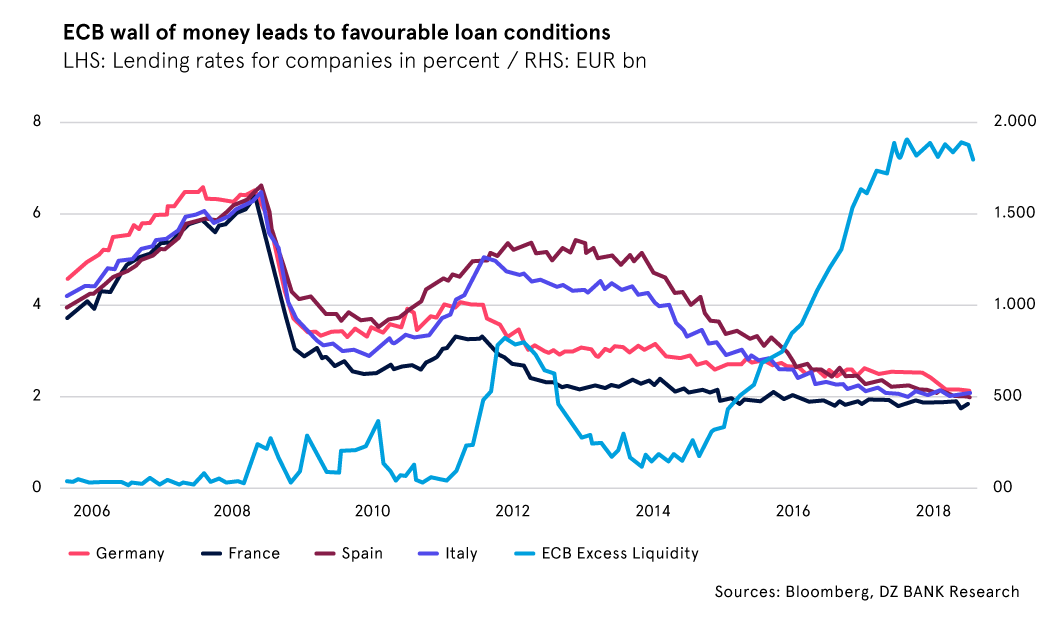

Such ample liquidity provision by the ECB (bond purchases / tender operations) has helped to ensure that extremely favourable financing conditions are currently prevailing across the eurozone. This can be gauged inter alia from credit conditions for loans to companies: where the variable interest rate for bank loans of up to EUR 1 million was standing at 2.71% at the outset of 2016, this is now down to 2.02%. When the TLTROs in circulation have fallen due, surplus liquidity in the euro area (currently EUR 1.85 trillion) will decline significantly because the central-bank liquidity made available to banking institutions within the framework of tender operations will flow back to the ECB. The associated shrinking of the ECB’s balance sheet will be tantamount to a considerable tightening of the central bank’s monetary-policy stance. There is therefore reason to be apprehensive that financing conditions for companies could deteriorate again. A driver here would be likely to be a jump in refinancing costs for banks. Where the latter were able, on a best-case scenario, to lock in central-bank liquidity for four years at -0.40% with the framework of TLTRO-II, current market rates are, at best, 45 basis points above this level in the four-year EUR swap rate segment. The spreads at which banks refinance themselves via swaps are often distinctly higher still, frequently running at clearly triple-digit basis-point levels, depending on the country and the bank involved. In the event of a deterioration, credit institutions would presumably endeavour to pass on higher financing costs to their customers. That could squeeze demand for loans and, correlated with this, bank lending. In a cyclical environment marked by little momentum, the monetary custodians will proably wish to prevent such a scenario. In the light of this, we think that there is a distinct probability of the ECB’s top echelons deciding to launch fresh long-term tenders in order to lastingly anchor surplus liquidity in the eurozone at a high level. Yet even if the purpose of a further liquidity injection appears to make sense, the question remains as to why market actors are already expecting such a decision to come through before very long; after all, the problem sketched above will only become a truly pressing one when the first TLTRO-II matures in June 2020.

The decision concerning the launch of fresh long-term tenders is subject to time pressure on account of regulatory requirements for banks. If the residual maturity of cash flows falls below a one-year horizon, they no longer count when certain parameters (net stable funding ratio / liquidity coverage ratio) are computed. This could compel banks from the European periphery, in particular, to shrink their balance sheets in order to comply with the respective statutory ratios. A possible side-effect of this would be a reining-in of bank lending. In addition, it could be conceivable that banks would prune their government-bond holdings, which might possibly entail higher risk premiums. In recent years, Italian banking institutions, in particular, have purchased a substantial volume of domestic sovereign securities in order to set up carry trades – cheap ECB liquidity is invested in BTPs, which actually generate a higher yield than bank loans. In the interim, apprximately 20% of Italian public debt outstanding is held by Italian banks. If credit institutions were to pare their bond holdings, this would presumably have a detrimental effect on risk premiums for corresponding sovereign bonds. In the light of this too, the central bank may consider offering new longer-term refinancing operations in order to forestall possible undesirable tensions.

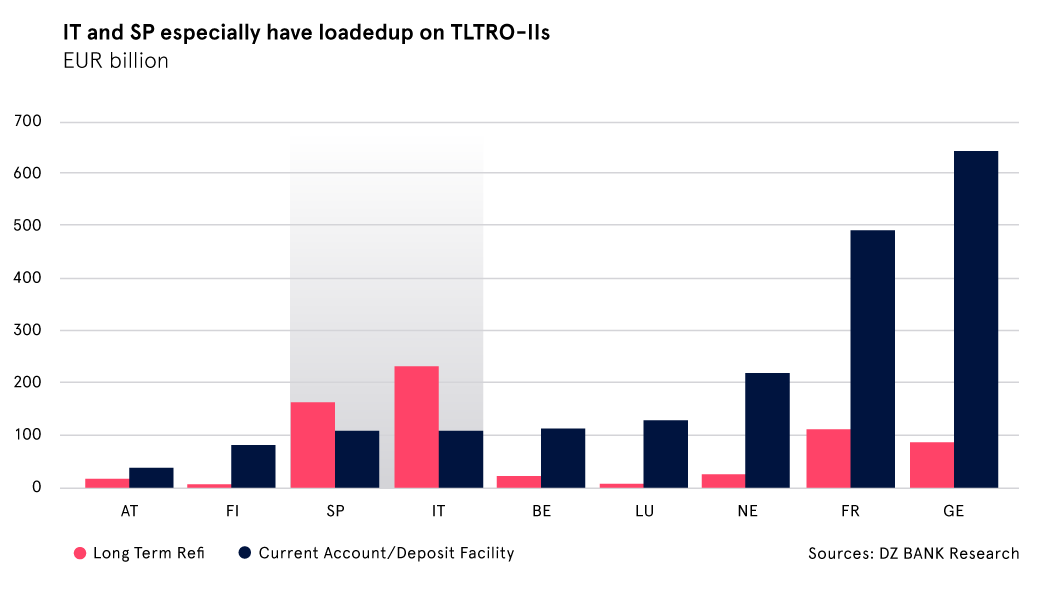

It should be noted in this connection that banking institutions in the various EMU member states depend to a very different extent on TLTRO-II liquidity. This is evident if one takes a look at the ECB’s statistics tracking the volume of central-bank liquidity taken up by individual EMU states within the context of longer-term tender operations (regular 3M tenders + TLTRO). Italian credit institutions are undoubtedly out in front here, with a 33% (EUR 239 billion) share of the aggregate tender volume currently outstanding. Spanish banks (23%, or EUR 167 billion) have likewise had ample recourse to longer-term ECB tenders. By contrast, banks from core Europe have tended to hold back. For example, French credit institutions have taken up a volume of just EUR 113 billion, while the share of their German counterparts is even lower at EUR 88 billion (12% of the aggregate volume outstanding). The extent to which Italian and Spanish banks are dependent on longer-term refi operations becomes even

clearer if TLTRO-II takeup is contrasted with commercial-bank deposits at the central bank. Where German banking institutions have currently parked around EUR 657 billion (!) at the ECB, the equivalent figures for Italian banks (EUR 88 billion) or their opposite numbers in Spain (EUR 119 billion) are noticeably lower. When the existing TLTRO-II loans fall due, Italian and Spanish banks, in particular, will face the challenge of closing the resulting liquidity gap. It ultimately becomes clear that Southern European banks would benefit especially from a fresh ECB liquidity injection. This, in turn, constitutes a certain quandary for the central bank which, as banking supervisor, necessarily has to avoid giving the impression of deliberately shoring up commercial banks in specific EMU member countries. This is also a delicate matter to the extent that the central bank is, at least on the face of it, mixing regulatory and monetary-policy interests and thereby risking damage to its credibility.

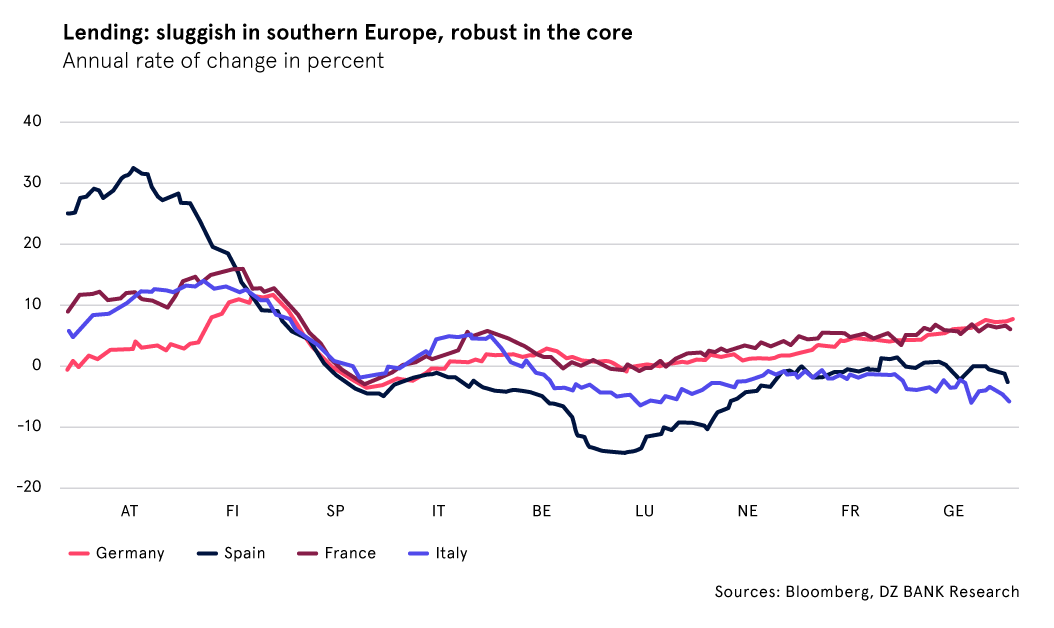

Ultimately, we assume that the ECB’s principal justification for the launch of fresh long-term tenders will be the halting pace of bank lending in Southern Europe. Where bank lending to the corporate sector is on a stable growth trend in Germany and France, it has actually been heading downwards again of late in Spain and France. Additional central-bank liquidity could at least make a contribution to preventing that downward trend from becoming more pronounced.

However, the central bank will be unlikely to be reckless when taking a decision in favour of fresh long-term tenders. TLTROs are not uncontroversial in the ECB Governing Council. Although tender operations certainly helped in the past to restore the disrupted monetary-policy transmission mechanism, they do, at the same time, aid and abet the moral hazard problem. After all, especially banks in the European periphery have, in the past, used favourable central-bank liquidity to set up carry trades. A new liquidity injection would make the ominous “bank-soverign doom loop“ even more manifest. In principle, this would make the ECB vulnerable to blackmail if one of these two actors were to run into turbulence.

We could nevertheless imagine that the monetary authorities will decide to administer a fresh liquidity injection at the next Governing Council meeting, scheduled for 7th March. The expected downward revision in the ECB staff’s economic-growth and inflation projections ought to make it easier for Team Draghi to justify the need for further liquidity measures. However, the interest-rate bonus linked to net lending could turn out to be somewhat less generous than in the terms of the current TLTRO-II operations in order to signal that the ECB continues to see itself on the long road back to monetary-policy normality. On the other hand, the central bank may seek to deflect criticism arising from its role conflict as bank regulator and monetary custodian by making the terms of the new TLTROs less generous. It therefore seems quite possible to us that the monetary authorities will decide to dispense completely with an interest-rate bonus, instead (for example) tying the trend in lending to the maturity of the tender operations. For instance, the maturity of refi operations could be extended from 24 months initially to 48 months in the event of credit institutions satisfying certain framework conditions regarding the trend in net lending. Even in the absence of an interest-rate bonus (fixed rate of 0%), this would nonetheless be attractive for banks. The favourable central-bank liquidity could continue to be counted when reporting key business ratios over the longer maturity period of the tenders, and banks would not have to refinance themselves on the capital market at higher rates. But one rather interesting question remains: whether fresh targeted longer-term refinancing operations would merely delay the ECB’s endeavours to normalise its monetary policy – or whether such endeavours have, in fact, been completely in vain.